Laibach's use of Slovene cultural imagery is well-known, yet this was always balanced and contradicted by a simultaneous and extensive use of Yugoslav references. Even as it asserted Slovene culture in the most spectacular form yet seen it retained an ambivalent relationship with its Yugoslav context. Twenty five years after the death of Tito and the creation of Laibach, it may now be time to begin to re-assess Laibach's relationship with Yugoslavia. Now that Laibach is a fixed (though still controversial) part of the Slovene cultural pantheon, the extent to which it shaped and was shaped by the Yugoslav environment is often overlooked.

Slovenia was an exception within Yugoslavia but Yugoslavia itself was a huge exception at the heart of Europe. The unique and sometimes almost structurally surreal features of Yugoslavia would provide fuel for Laibach's explorations of the "relationship between art and ideology." From 1945-48, Tito's new regime pursued Stalinist policies of collectivisation and industrialization, but in 1949 Tito broke with Stalin, and from this period on Yugoslavia began to carve out its unique "non-aligned" path between the Eastern and Western blocs. In the fifties, Tito settled on a tolerant cultural policy allowing all but the most extreme forms of Western culture. By the sixties, there was an established Yugo-Rock scene (including music openly praising Tito and the system), radical conceptual art was gaining a place alongside the official artistic modernism seen in Zagreb and Belgrade, and many Yugoslavs, particularly Slovenes, travelled fairly freely to the West. The early to mid seventies were a contradictory period. The Croatian nationalist movement led to an ideological crackdown and increased authoritarianism. On the other hand, there was a consumer boom fuelled by Western loans and de-centralisation of the hyper-complex Yugoslav self-management system theoretically allowed for more regional initiatives and freedoms, especially in Slovenia. A 1972 UNESCO publication on Yugoslav cultural policy (issued while purges were still occurring within the country) made utopian-sounding claims which in fact were not entirely fanciful:

"...development in all spheres, including the cultural one, is directly antithetical to Statism... The socialization of culture, which is the general objective of this [Yugoslav cultural] policy, calls for the change of both the external and internal relations which formerly existed in the administrative budgetary system. It denotes a comprehensive programme of "deStatization" of all spheres of public activity and the gradual democratization of relations between cultural institutions and society as well as the democratization of relations within the institution itself... It further implies the creation and development of a democratic cultural climate which will make a free competition of creative forces possible, ensure the enforcement of the principle of selectivity, the emancipation of evaluation from bureaucratic subjectivism and restrictions, while concurrently heightening the sense of responsibility for cultural and social development of the community as a whole." 1

Yugoslavia had become an incredibly complex space, supporting a vast range of mutually contradictory cultural and political agendas. Arguably, it collapsed not because it was too primitive but because it was too sophisticated. In 1977 the provincial calm of Ljubljana was shattered by the arrival of Punk, graffiti and other decadent Western phenomena. The Slovene Punk scene soon became notorious throughout Yugoslavia and within a few years Ljubljana would become a counter-cultural centre for Europe as a whole, not just Yugoslavia. In May 1980 Tito died and the rotating collective presidency system that followed him soon began to unravel. Economic recession and the calling-in of Western loans forced Yugoslavia to accept harsh terms from the IMF, creating much social tension which translated both into extreme subcultures and growing nationalism. Less than a month after Tito's death, a group calling itself "Laibach" was founded in Trbovlje, the heart of Slovenia's industrial "Red Districts", well known for their militant political history.

Bloody Ground… Fertile Soil

From a British perspective there is much about Yugoslavia in the sixties and seventies that seems familiar, not just the largely shared pop culture. In both countries the heroic myths of World War Two were inescapable - war films, books, comics and toys were omnipresent and anything German had a taboo quality. As a country that actually experienced a brutal Nazi occupation, it was more understandable for Yugoslavia to keep alive old memories, but even so for those born in the sixties the saturation of the culture by images of the war became oppressive and alienating. This cultural overkill manifested itself in Laibach's ambivalent use of Tito and near simultaneous posing as both Partisans and Fascists (Yugoslav children's equivalent of Cowboys and Indians). Laibach then, emerged from a context shaped by Yugoslavia's complex and increasingly dysfunctional official ideology, the noise and pollution of local heavy industry, vivid memories of Nazi violence, Germanisation and a small radical cultural scene open to Punk and radical art. This mixture was as unstable as, and a reflection of, the volatility of the Yugoslav state itself.

This environment could be overwhelming and alienating, but the unique characteristics of Yugoslavia also provided the means to interrupt the simultaneously oppressive and banal nature of daily life. The response of those who came together under the name "Laibach" was to combine the culture that inspired them – Punk, industrial, classical and electro-acoustic musics, radical and national art with the alienating presences of history and ideology. Laibach assumed a "right to reply" to its environment and to try and make sense of it. Laibach's German name was already a grave provocation, reactivating historical memories of Germanisation and collaboration. From the start, Laibach was a mixture of experimentation, provocation, and a systematic analytical approach intended to break through actually existing normality and explore "the relationship between art and ideology."

Even the compulsory military service that many dreaded spurred the development of Laibach. During his posting outside Belgrade Dejan Knez made contacts with the city's radical cultural scene and the first Laibach exhibition was staged there. During early Laibach concerts military smoke bombs were used and Laibach's uniforms were based on Yugoslav army fatigues. After military service, members of the group re-joined the emerging Punk/alternative scene in Ljubljana and soon became its most extreme element. In 1981 the Slovene authorities and much of the media ran a disinformation campaign against the Punk scene, claiming it was a Nazi subculture. As Laibach's manager pointed out any new or radical form such as Punk was automatically denounced as "Fascist". In these circumstances it was more than obvious that there was nothing to lose by including Fascist imagery within a culturally provocative strategy – no matter how correct it was it would likely be denounced as "Fascist" anyway.

However, much of the material Laibach used actually derived from Yugoslav and Slovene history, and in particular from self-management and the socialist heritage of Trbovlje. In short, Laibach treated its entire ideological and historical context as a Duchampian "ready-made" with which to "deterritorialize" or "make strange" Yugoslav reality. Influenced not just by Kraftwerk's "industrielle Völksmusik" but by Throbbing Gristle, Laibach produced tone pictures of the decaying dystopian heavy industry they grew up with. Like Throbbing Gristle, Laibach was as much a conceptual performance unit as a group and neither group ever claimed to be musicians. On stage, Laibach experimented with oscillators, feedback and carried out primitive sampling using old turntables. Even for radical and Punk audiences the result seemed extreme, and often provoked violent responses.

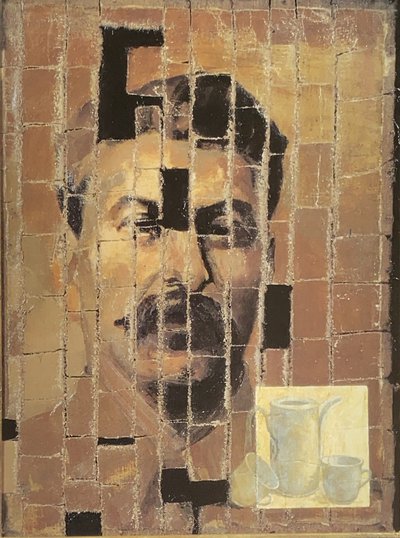

Laibach also "sampled" the actual language and texts of self-management, which was experienced by many as corrupt, complacent and decadent – an unstable mix of officially-encouraged consumerism plus residual Stalinism and nationalism. Laibach quoted from Edvard Kardelj, the Slovene ideologist of self-management and also from Tito. Samples of Tito speeches were played at concerts and appeared on Laibach's tracks Decree and Država (The State). When Laibach's first album was issued in Slovenia, Tito's voice was excised by censors (rather than cover this up, Laibach left an audible gap to highlight this enforced absence). Laibach's use of Tito actually referred back to a phenomenon that marked the Yugo-rock scene in the seventies: kitschy ballads by artists such as Rani Mraz extolling Tito, Brotherhood and Unity, even the self-management system itself. These were the mainstream precedents for the use of ideology in popular music. Laibach's politicised interrogation of popular music revealed the extent to which it had been compromised in its relations to the system. Laibach particularly used statements dealing with non-alignment, Yugoslavia's "third way" policy between the Eastern and Western blocs. Non-alignment provides a metaphor for understanding Laibach – an oscillating state that like non-aligned Yugoslavia seems to contain the characteristics of two opposing but related blocs – left and right.

In a notorious appearance at the Zagreb Biennale of New Music in 1983 with the British groups 23 Skidoo and Last Few Days, Laibach created a major scandal. Laibach projected images of the Partisan struggle and Tito alongside porn clips and their oppressive din. The concert was halted by police and military officials and the group escorted onto a train for Slovenia. This created a media scandal and Laibach issued a statement explaining its methodology. Laibach claimed its "provocative interdisciplinary action" applied to ideological and historical trauma encouraged "…critical awareness" in those exposed to it. 2 Laibach explained itself in terms of modernist conceptual art practices and referenced amongst others the work of Nam June Paik, Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage. Laibach's use of these elements was a commentary on the presence of Western avant-garde ideologies in Yugoslavia and severely complicated any definitive political classification of the group.

What Laibach was enacting was a type of mystifying demystification, illuminating the contradictions and normally hidden noise of ideology, using its irrational, uncanny aspects to build its own mystique and evade definitive categorization. Alongside the paramilitary and ideological elements, Laibach also introduced more esoteric symbols, and alluded to Slavic paganism, exorcism and the occult. The implication of this was that just below the surface of Yugoslavia's rational modernist reality lay all manner of irrational forces and unprocessed historical tensions. The pandemonium of its early concerts represented a manifestation of these tensions. Laibach repeatedly claimed to be carrying out exorcistic practice, and referred both to Catholic ritual (in Vade Retro Satanas) and to the shamanistic actions of Beuys, which were also intended to heal the psychic wounds inflicted by the war (Laibach is also an example of Beuys' theories of artistic "infiltration" and, most relevantly, "social sculpture.")

Cultural Oscillation

Under Tito, Yugoslav foreign policy oscillated between East and West, at times closer to one than the other. When the individual republics made final incompatible choices about their geopolitical alignments and the oscillator (embodied in the figure of Tito) was shut down, Yugoslavia ended. Previously, Yugoslavia could never be definitively included in any category but its own, ("non-aligned, self-managing") despite (or because of) the fact that in some respects it identified very closely with other systems. The same is true of Laibach. It deliberately contains elements that seem to leave no possible doubt as to where it (really) stands politically and culturally, yet also contains others which negate or are antithetical to these, but which could also be taken to definitively "prove" its stance. At the conceptual-symbolic level, Laibach both is and is not what it appears to be. Just as it refuses to make a choice between external categories, Laibach simultaneously confirms and denies its "true" nature. Like self-management, it carries out a type of mystifying demystification of the ideological contradictions at its heart, covering ideology with a layer of its own reality (and also vice-versa.)

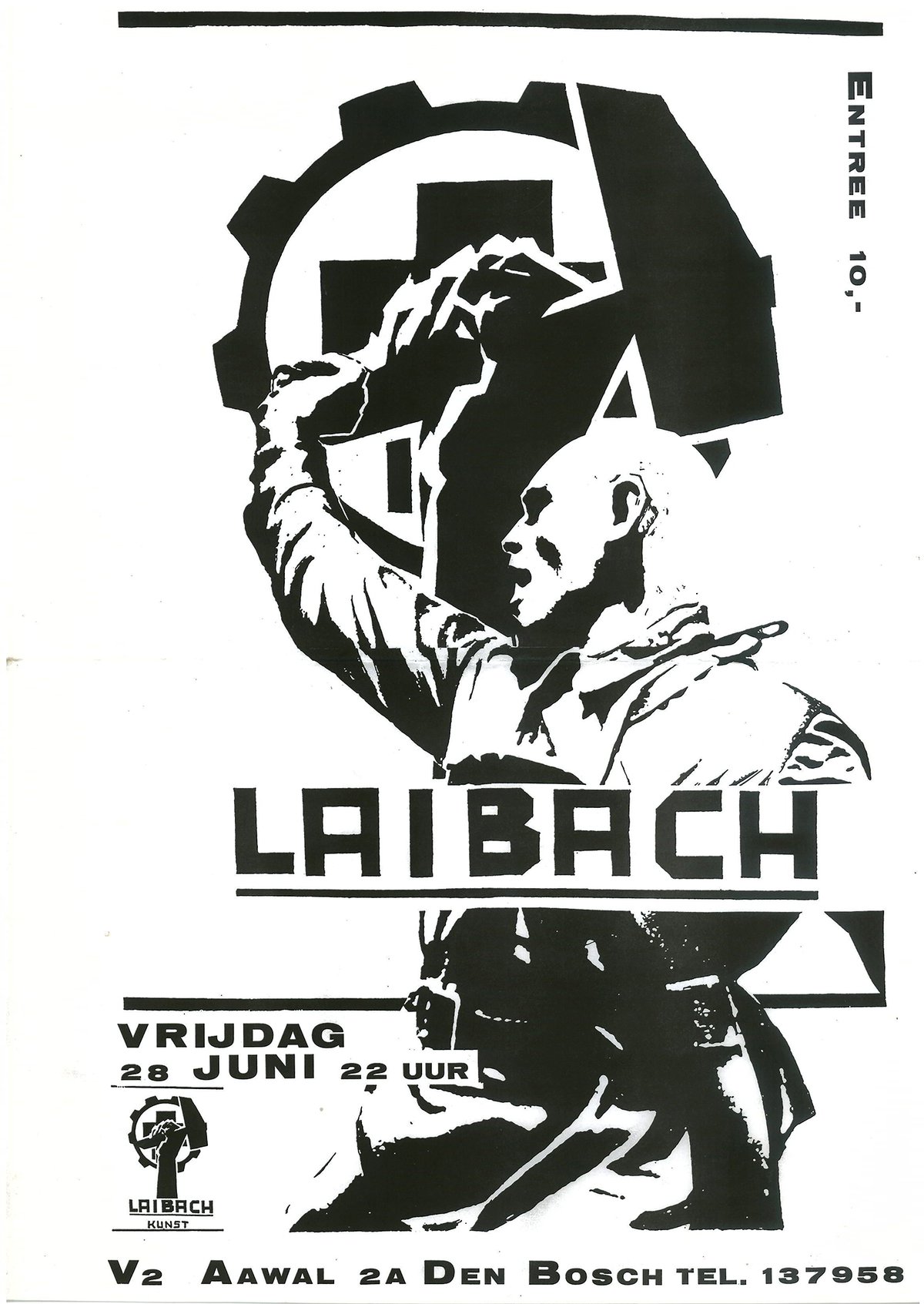

Laibach, Free Yugoslavia, 1984

Laibach, Free Yugoslavia, 1984

Like the diplomacy of the old Yugoslavia, Laibach is involved in a playful or provocative dance or flirtation with a series of ideologies and processes that is never "consummated" because Laibach never finally chooses. Ultimately, Laibach never comes to a halt or sets up home in any camp but it's own. Elements that it seems to concretise in monumental form are actually set into flux, whilst trivial or ephemeral sources (Western pop) are simultaneously monumentalised. Laibach does not pretend to "originality" or conceal its sources, yet neither does it accept them as the basis for categorization. The mechanics of this process only become clear through detailed interrogation of the works and their construction.

No matter how closely Laibach engages with a certain quality or system, the presence of this is as likely to be a means of dis-association as association. What is in question is even a type of dis-identification through over-identification. Laibach's use of particular political discourses or of ideological themes such as heavy industry are never one-dimensional and can imply both negative and positive attitudes simultaneously. In as much as there is "a" final resolution of these contradictions it is either in the onlooker's perception or within the collective framework of NSK as State and "Gesamtkunstwerk".

State Barbarism

"BARBARIANS ARE COMING, HEADING YOUR WAY.

THE EVIL IS RISING INTO YOUR DAY.

BARBARIANS ARE COMING, HEADING YOUR WAY.

THE EVIL IS RISING, KNEEL DOWN AND PRAY.

THEY'LL CONQUER YOUR COUNTRY

AND MAKE YOU ALL SLAVES,

THEY'LL BURN DOWN YOUR HOUSES

AND RAVE AT YOUR GRAVES.

YOU'D BETTER GET READY,

YOU'D BETTER BEWARE.

BANGING AT YOUR WINDOWS,

BARBARIANS ARE HERE

BARBARIANS ARE COMING, HEADING YOUR WAY.

THE EVIL IS RISING, KNEEL DOWN AND PRAY.

BARBARIANS ARE COMING, HEADING YOUR WAY.

WHATEVER YOU TOOK FROM THEM –

NOW YOU WILL PAY"

Laibach – Now You Will Pay 3

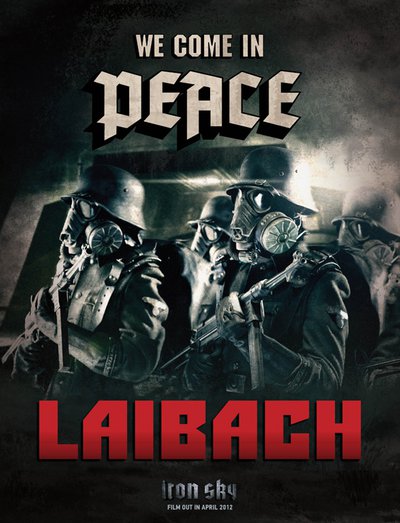

Besides sampling the symbols of the Balkan/Yugoslav modernism of self-management, Laibach also sampled the repressed catastrophic forces that would emerge from its disintegration. Laibach appear at one level to embody both imaginary and real Balkan pre-modernism, fleshing out Western fantasies of the Balkans as the location of dark, spectral archetypes of war and primitivism. In the promotional video for the WAT album, Laibach emphasise that they have always proudly called themselves barbarians, coming to the West stealing sounds, concepts and images at will. The song Now You Will Pay stages an infinitely deferred threat-promise of a wave of revenge, violence and destruction coming from the East, suggesting a counter-colonisation of the supposedly strong by the supposedly weak. Laibach's sensory-conceptual violence is necessary both to recapitulate the hidden violence of cultural exchange under neo-liberal market conditions and to challenge the dominance of Anglo-American rock culture, the populist cultural façade of neo-imperialism.

On the one hand, the West is captivated by what it sees as exotic or primitive Balkan cultures, but on the other it finds it hard to admit a fascination for anything too elemental, archetypal or dangerous. Laibach's work continues to express the violent and unresolved tensions between the old Yugoslavia's simultaneous aspirations to be a worker's state and an ultra-modern cosmopolitan society. This explains the jarring shifts in Laibach between archaic primitivism and hyper-complex language and techniques. Laibach's self-assumed barbarism was in effect an expression of the state's latent barbarism. It alluded to the fact that while Yugoslavs like to see themselves as relatively sophisticated they were still seen as backward and primitive by many in the West. It also hinted at the barbaric roots and potentials of the Yugoslav state.

The paradox is that while Laibach is simultaneously blamed and celebrated for its supposed role in the ending of Yugoslavia, it has been the most distinctive and internationally successful phenomenon to emerge from Yugoslavia. The fact that some in the West seriously perceived Laibach as Yugoslav cultural ambassadors illustrated the strength of the group's ambivalent connection with its host state. Laibach simultaneously represented the best and worst of late Yugoslav culture, and will always colour people's perceptions of this period. Of course, Yugoslavia was simply one element in Laibach's "palette", but the fertile chaos of the old country provided as many opportunities as restrictions, and without the Yugoslav context Laibach would have assumed a very different form.

Parts of this text are based on the lecture "Barbarians are coming!" given at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, 15th March 2004.