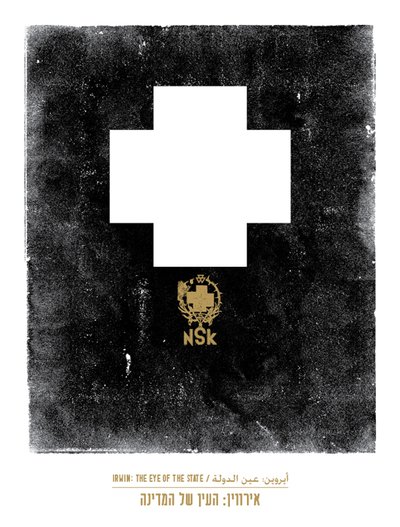

It’s time for a new state

Some say you can find happiness there

To be able to tell the story of the billboards, I have to return to Lagos, where Miran Mohar and I travelled to in July 2010. We went there because of the large number of applications for the NSK passports that we had received from Nigeria in the preceding years. They started trickling in, but in a relatively short amount of time, the number of applications exceeded a thousand and continued to grow. Since most of the applications came from the same city, it could be concluded that the information about the passport had spread byword of mouth. It was not particularly expensive, but for the inhabitants of the so-called third world, its price was certainly not negligible. At the same time, it did not seem likely that their interest in obtaining a passport would be limited to the field of art.

When we arrived in Lagos, we soon noticed the billboards, in Slovenia we call them “jumbos”, for which it was not clear what they were promoting. In fact, we were alerted to them by the hosts, who proceeded to watch us suspiciously, as if believing that we were somehow responsible for them. The large red billboards read: “Time for a new state”, and under that: “Some say you can find happiness there.” Just that; neither the producer nor the product was listed. We asked the hosts from the ICA (Institute for Contemporary Art) what the billboards were for, but nobody could answer us. Jude mentioned a refreshing beverage, but he was not sure which one it was supposed to be, local or foreign, if at all. It was one of those campaigns that develops a narrative through a series of appearances, only disclosing what it is selling at the end. Along with the billboards, full-page newspaper ads were also used. The only difference was that the horizontal composition of the billboards was replaced by a vertical one in the newspaper. Considering that the name of the NSK state is in fact theNSK State in Time, it is easier to understand why our hosts found the connection between the billboards and the NSK State in Time, which was the sole reason for our visit to Lagos, plausible. It seemed as if the billboards were there because of us, because of our project.Among the several interviews conducted with the NSK citizens, there is also one in which the interviewee, when he learns that the NSK state has no territory, replies: “But my friend has been there,” as well as one in which the interviewee describes the NSK state in the words from the billboard: “Some say you can find happiness there."

After returning to Ljubljana, we gave the journalist, who wrote an article about our trip, a photo of the billboard with a panorama of Lagos in the background, which was published in a newspaper. After the piece was published, reverberations could be heard from a long-time collaborator that we had really gone overboard this time. Is it not too cynical to do such a project, he asked. But the billboards in Lagos were not our project, even though they seemed to be and we took them as our own.

Just a few months later, in October 2010, we found out whose billboards we had adopted. The first congress of the citizens of the NSK State in Time was being held at the time in Berlin, where we met up with Jude again, who was there as one of the delegates. The mystery was revealed: the billboards belonged to The Coca-Cola Company.

In September 2011, we participated in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Moscow, which was, after a long time, again curated by Viktor Misiano. As part of our contribution, we proposed a propaganda campaign – the organisation of a billboard and a full-page advertisement in one of Russia’s newspapers – for a country where happiness could be found, this time in Russian. The director of the museum expressed doubts that such a campaign could be well received by the authorities.*1 Nevertheless, he agreed to a12x6 metre billboard suspended on the facade of the museum. But the billboard was removed after just two days. The reason was the multitude of calls from people who were interested in what the billboard actually conveyed.

Perhaps I am not informed well enough, but it seems really strange that such a campaign was conducted in a deeply destabilised “third world” country, which Nigeria undoubtedly was at the time, as actions of this kind would be just as, or even more, unacceptable in more developed parts of the world.*2 This kind of campaign is very close to something that can be understood as an aggressive act, if not an act of aggression.*3

Borut Vogelnik

Ljubljana, 2014, 2018

IRWIN: Time for a new country, Celje, 2020 photo: Tomaz Črnej

IRWIN: Time for a new country, Celje, 2020 photo: Tomaz Črnej

IRWIN: Time for a new country, Celje, 2020 photo: Tomaz Črnej

IRWIN: Time for a new country, Celje, 2020 photo: Tomaz Črnej

*1: Elections were being held in Russia at that time.

*2: I looked through the history of the propaganda campaigns by The Coca-Cola Companyon the web but could not identify this campaign in the review I found.

*3: Nigeria is one of the countries in which Cambridge Analytica operated. In 2015, CA actively participated in the presidential campaign there. Source: The Guardian (international edition).

Article title: Cambridge Analytica’s ruthless bid to sway the vote in Nigeria / The Cambridge Analytica file: Carole Cadwalladr, 21 March 2018.

Quote: It was a methodology honed and developed in the company’s defence and military work – the fifth dimension of warfare, defined by the US military as “information operations”.

Quote: Seven individuals with close knowledge of the Nigeria campaign have described howCambridge Analytica worked with people they believed were Israeli computer hackers. Their testimony paints an extraordinary picture of how far a western company would contemplate going in an effort to undermine the democratic process in a country that already struggles to provide free and fair elections.